- Share via

On the Shelf

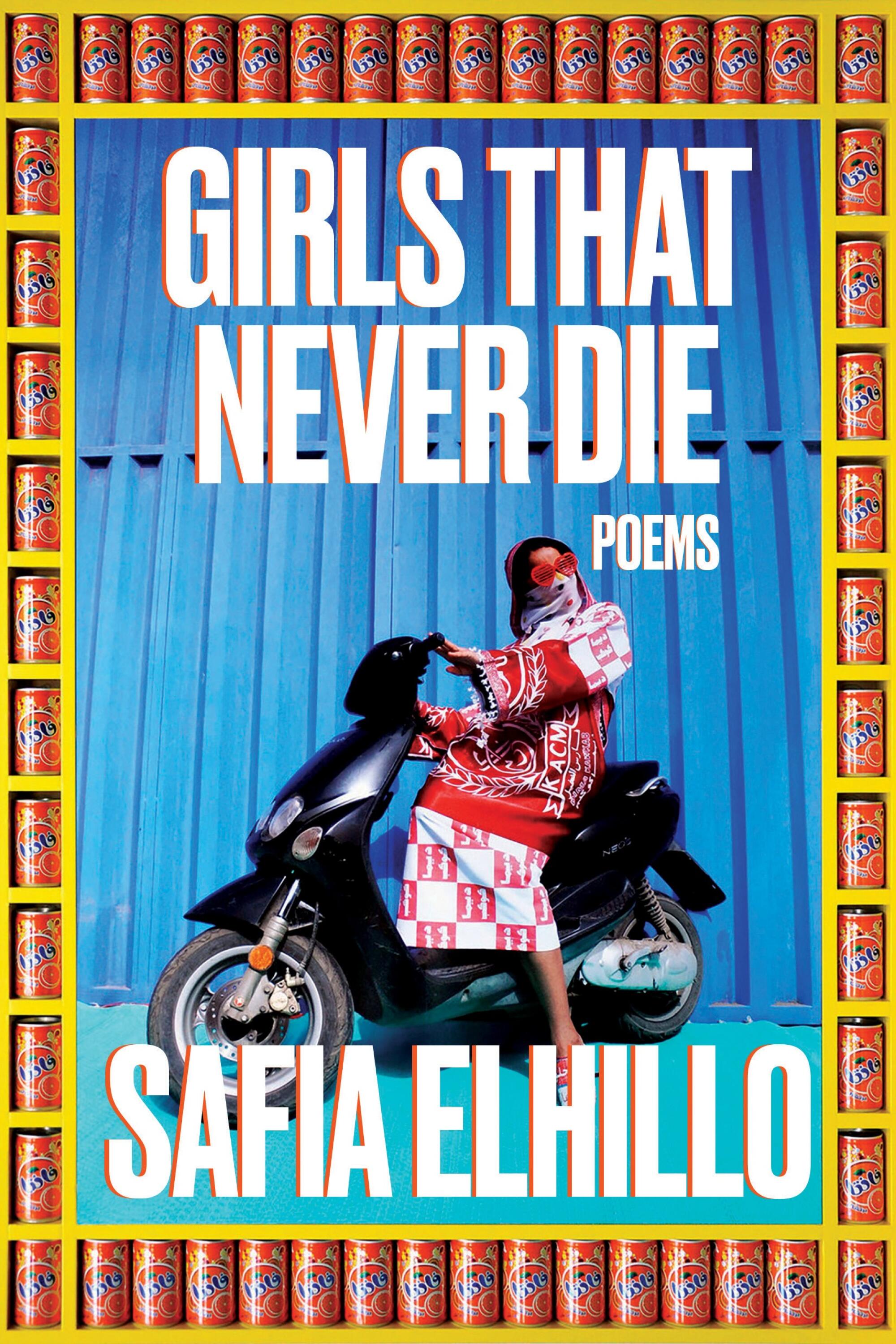

Girls That Never Die: Poems

By Safia Elhillo

One World: 144 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

If you search “Safia Elhillo” on YouTube, the first entry you’ll see is a video from 2016: a reading of her visceral, mesmerizing poem cycle “Alien Suite” at the 2016 College Unions Poetry Slam Invitational.

This particular video has more than 150,000 views, but what makes it different from other slam poetry videos is the length. Elhillo recites her verse for 16 minutes to an audience we cannot see, though we hear their collective murmurs and snaps.

Her voice is both sweet and expansive — helium and honey — as the Sudanese American poet speaks of Arabic study, of her identity in relationship to nation-state and family. And even though she never raises her voice, the sincerity of her stories pulls you deeply in.

This effect is only magnified in person. During a recent meeting in her Los Angeles apartment to discuss her fearless second collection, “Girls That Never Die,” Elhillo, now 31, talked expansively about everything from her artistic evolution to the challenges of finding someone who can properly do her hair. She exuded the supreme self-awareness that marks both her performances and her online presence. Though she is also arguably one of the most fashion-forward poets on Instagram, for this interview she eschewed her usual vibrant colors and eclectic prints for a loosely fitted cream-colored dress that she said feels more authentic to how she relaxes at home.

‘The Mic,’ a fledgling open-mic night for queer poets and performers, has found an incongruous — but in fact ideal — home at Micky’s nightclub.

Throughout our conversation, her somber expression often cracked into a wide grin, revealing the joy that bubbled underneath — as it does below the surface of her writing.

And it is her written poetry that now makes impressions. Over the six years since she appeared in that video, Elhillo has gone from winning slams to winning book prizes. Her first collection of poems, “The January Children,” won the Sillerman First Book Prize; it was followed by a young adult novel in verse, “Home Is Not a Country,” that was long-listed for a National Book Award and awarded a Coretta Scott King Honor. These books examined belonging in a postcolonial world and creativity in defiance of manmade borders.

“Girls That Never Die,” out last week, has the makings of a breakthrough. Compared with her earlier work, it’s less about nostalgia and more explicitly about shame and silence in relation to Muslim girlhood. It also signals a change in style and perspective. Where she used to mirror speech by writing without punctuation or capitalization and used frequent caesuras, or rhythmic pauses, instead she opts for prose poems to depict a set of hard facts more directly — and to more effectively critique violence against women in her community.

Poems like “Infibulation Study” delve into cultural taboos like genital mutilation. Others leaven the collection — again that balance of gravity and joy — with shrines to womanhood and solidarity. “Ode to My Homegirls,” for instance, depicts the mischievousness and protective loyalty of young women.

Opening up about misogyny in Muslim culture bears a risk Elhillo well understands: A white audience might find its stereotypes about Islam reinforced. But for the poet it’s far better than not speaking up at all. “Ultimately, silence is not going to protect any of us,” she said. “If harm is being done, harm is being done. Me keeping quiet about it is not going to make the harm disappear.”

Elhillo isn’t writing for a white audience anyway. “Girls That Never Die” is for her aunts and uncles and the religious community she grew up in. It is not, she emphasized, for those who have already made up their minds about Islam or girlhood or the intersection of the two. “I’m really tired of trying to prove my humanity and the humanity of my community to people who don’t hold that as a core belief,” she said.

That lack of eagerness to cater to a wider (and whiter) audience is exactly where Elhillo’s power resides. She said she never looks at sales numbers for her books; it’s not her responsibility. Instead she prefers the freedom to write with specificity about being Black, Sudanese and Muslim in its myriad complexities. Any other reader is likewise free to listen in.

“The plan is to write as if only the people I’m talking to are going to read the poem. … Then everyone else is eavesdropping on what is hopefully a super-interesting conversation,” said Elhillo. “I don’t have an ambassadorial bone in my body. I’m just minding my business, minding my people’s business.”

Bay Area novelist Ingrid Rojas Contreras tells of how a head injury led her to revisit the shamans in her life — and her native Colombia.

As a bilingual writer, she allows untranslated Arabic to interweave itself naturally into the fabric of her verse. She regularly references the lyrics and stories of iconic Arab singers, especially the Egyptian artist Abdel-Halim Hafez in “The January Children.” Elhillo references the word asmarani, a term of praise and adoration for dark-skinned people, to describe her own Black identity in an Arabophone world.

The Muslim American experience is essential to her work but never essentialized; Elhillo’s poems are too multifarious for that. She does acknowledge the influence of the Quran in one respect; allusions aren’t explained, and the reader (eavesdroppers and insiders alike) is expected to do the work to understand the context.

Elhillo is a second-generation U.S. citizen, but she describes herself as an outsider writing at a distance from American culture. It makes sense when she talks about her upbringing in the U.S., surrounded by a community of Sudanese immigrants in the Washington, D.C., area and going to Arabic school on the weekends. But she’s still informed by — and trained in — the American poetic tradition.

“I think of like a Frank O’Hara, just that frankness in that plainspokenness,” she said. “The colors are really solid — that feels very American.”

Performance is also still in her bones; reading her work aloud is the first step in her editing process. “Your ear can always catch something that your eye might not be able to.” The existential crisis every poet faces is when to stop editing. For Elhillo, that moment arrives when she’s able to read the poem in front of other people. As far as she is concerned, the dichotomy between the stage and the page is a false one.

Still, “Girls That Never Die” is more structured than her earlier work. In part, incorporating new forms was a way to cope with the pressure to live up to her earlier work — a way of lowering the stakes. “I was like, ‘Well yes, this contrapuntal sucks because I’ve never written before,’” said Elhillo. “Instead of being like, ‘This poem is bad because I myself have no value as a poet.’”

As her second collection moves out into the world, Elhillo’s life continues to evolve in ways that will surely expand her work. Having moved through different cities — from D.C. to New York for school, then to Oakland for her Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford — she’s always found a local Sudanese community that’s grounded her. After moving to L.A. last year during the pandemic, she found relief in the sunny weather and close friends, but she has yet to find her local Sudanese community.

Elhillo has found a way to keep up with her Arabic, though: “All I have to do is go to a hookah bar I’ve never been to before, place my order, wait five minutes and then [ask], ‘Where are you from?’ And then the floodgates open, you know?”

The poet is more focused these days on creating such new rituals, simple pursuits that mark a life’s transitions. Her aunt, who would regularly cut her hair, recently married and moved to Sweden, so she needs to find a stranger she can trust with her split ends. She also needs more bookshelves for the dozens of books on the floor of her office. And she’s finally learning to drive after putting it off in favor of learning how to write a contrapuntal.

For decades, poets without legal status were excluded from prizes. A group called Undocupoets changed that — and then founded a prize of its own.

A homebody at heart, Elhillo loves hosting intimate gatherings of close friends in her living room — but when she goes out, it’s always in style. On Instagram or out in the world, fashion is, for her, just another source of self-expression. Much like her poetry, her clothes borrow from a variety of influences.

In navigating her new life, the immediate present makes more of an impression on this history-focused poet than ever before. Expect to see more of it in her next collection, to be published next year.

“In the poems I’m writing now, a lot of them feel more mundane in a way that feels nice,” she said. “I’m taking my little walks and making observations and it’s nice to know that’s deserving of poetry too. It doesn’t have to be some enormous rupture in history.”

Deng is a queer Taiwanese/Hong Konger American poet and journalist born and raised in the San Gabriel Valley.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.